Playing Twinkle Twinkle Little Star fingerstyle

Introduction

If one whistles any single-note melody, whether it's Let It Be, Auld Lang Syne, or Twinkle Twinkle Little Star, is it possible to build a multi-note arrangement, with nothing but that starting, primordial goop of the single-note melody? Imagine being able to play a fingerstyle arrangement to any melody that springs into your ears.. how freeing that would be!

This skates into the realm of harmonization, which means dressing-up a single-note with other complementary notes. Peering into the past, piano-masters such as Art Tatum & Erroll Garner could, according to recollectors, listen to anything and play it back, whether it was a romantic-era classic, or popular tunes of the time, marking out the melody, yet somehow intuiting complementary notes to play with other fingers of the right-hand, and the left-hand. Even earlier, Bach and Mozart purportedly would set their hands to the keyboard and improvise contrapunctal melodies, with many of their transcribed classics simply being like recordings of their improvisations.

Clearly then, it must really be possible to train the brain to spontaneously improvise multiple notes at once. Also, if it's assumed that this activity takes place on a lower-level, within the brain, before even reaching the instrument, then it must be possible to do on any instrument capable of sounding-out more than one note at one time, such as a guitar. To prove this point, listening to albums such as Virtuoso #4 by Joe Pass, where one can practically follow Pass' stream-of-consciousness, figuring out fingerstyle arrangements on-the-fly, this is verified.

But then, how is this possible? Where can one even begin?

Taking on the task with twinkle

As one of a likely infinite number of ways to reach a level of improvising harmonies, this guide will focus on harmonizing the melody of Twinkle Twinkle Little Star; since it's such a known melody, one doesn't have to exert extraneous brainwaves towards recognizing the melody, instead jumping straight towards the concept of harmonization.. which implies practical consequences such as improvising fingerstyle arrangements and so on.

The process

To crack this nut, which is like veering into the abyss, the old adage, "let the melody be your guide," will be relied upon; it's taking a leaf from the tree of old jazz players when they spoke of improvising on complex chord changes; it works here also.

- Decide where to play the melody. It can be anywhere on the neck & on any string

- Use your ear to determine the root-note/tonic from the melody

- Figure out the chord progression using your ear (this step will be skipped and the chords will be provided here)

- Using the chords, determine the scales to draw from compatible notes

- Add those notes into the orbit of the melody to form harmonizations

Much like learning a board game, reading through the manual/instructions, even taking notes on it, will only go so far. Instead, just playing a first-turn, even if it's confusing along the way, feels like a faster route. In that vein, this guide will comb through 5 cases. While it might seem hazy and lacking direction with the starting 1st-case, keep hanging on, and by the 3rd, 4th, or 5th case things may feel more motivated.

Case 1: Key of A / 3rd String

Remembering that the goal here is about unsolving the mystery of how to harmonize a melody, imagine you've started whistling Twinkle Twinkle Little Star, and, in the hopes of creating a fingerstyle/multi-note arrangement of it, you grabbed your guitar and noticed the starting note matches-up to the 2nd-fret of the 3rd-string.

From there, you branch-out across the same string, the 3rd-string, completing the melody. All told, it would look something like this,

i) What's the root note?

Recall that 'the process' states that one of the 1st harmonization steps (according to this guide) is using your ear to determine the root-note/tonic. That's something that takes a bit getting used to; it's a fundamental concept, yet one that's hard to talk about with words alone. Suffice it to say, the root-note is that note that seems to just sound "right", as if there's a particular gravitational pull towards it.

In this case, the root-note happens to be the 1st-note of the Twinkle Twinkle melody. For other songs, the root-note might be more obscurely nested within the melody (or not even present whatsoever, being implied instead). Fortunately, Twinkle Twinkle renders this step fairly pain-free.

More specifically for this "case #1", in standard tuning, the 2nd-fret of the 3rd-string happens to be the A-note. Since this A-note is the root-note/tonic, Twinkle Twinkle is in the key of A here.

ii) What's the chord progression?

The next step in this process is being able to assign chords for each melody note. Usually, the default method to scale this wall is by "googling" the chord progression for a song, but it's actually possible to use your ear also for this step. Similar to how you can "tell" when a blues song is about to transition into the IV-chord, or when the turnaround will "resolve" into the I-chord, it's possible to just feel when songs move to the minor-IV, minor-III, dominant-bVII, and so on. Undoubtedly, it helps to empirically know lots of where those sorts of chord 'changes' happen to build a mental library/map of how/where/'why' to use those chords.

For example, blues players get trained intuitively to feel changes from the I-chord into the IV-chord, to the point where they can improvise those chord changes when jamming other genres such as grunge. Similarly, classical players get trained to inuitively trained to feel changes from a minor-I-chord (played throughout the song), while playing the final bar as a major-I-chord, adding an interesting effect, to the point where this can be applied elsewhere also. The point here, although not wholly necessary for this guide, is that with time one can in fact learn how to apply chords of all scale degrees into a song with experience and practice; in other words, it's not witchcraft to just "inuit" chord changes with one's ear, simply by using the melody, without any use of "googling" for the progression. It's not necessary, but it's really freeing to develop that skill, because you can build chord progressions that might even be better than what's found on google. This is a key aspect of harmonization... namely "reharmonization", where you make personal decisions of the underlying chords, modifying the status quo. It's part of why the national anthem often sounds different with different renditions.

In any case, scrolling back to the simple, single-string transcription of Twinkle Twinkle back above, those are some chords one can assign to the melody; they're simply the I-chord, IV-chord, and V-chord, all played as major chords. Said loosely, the I-chord acts as the home base, the IV-chord adds a refreshing/different landscape to visit, and the V-chord acts as a turnaround chord to always lead back into the root.

iii) What scale(s) can be used?

The major-scale has 7-modes (ionian-I, dorian-II, phyrgian-III, etc...) where the ionian-I, lydian-IV, and mixolydian-V chords all happen to be major chords (while the II, III, and IV chords happen to be minor chords). Said quickly, this just means that the arpeggio notes of those modes (the 1st, 3rd, and 5th degrees of the I, IV, and V modes/scales) spell-out major chords.. namely, the root (I), the major-3rd (III), and perfect-5th (V). Why is that mentioned here? For this assigned chord progression, it justifies the use of the A major-scale as one scale from which harmonized notes can be drawn.

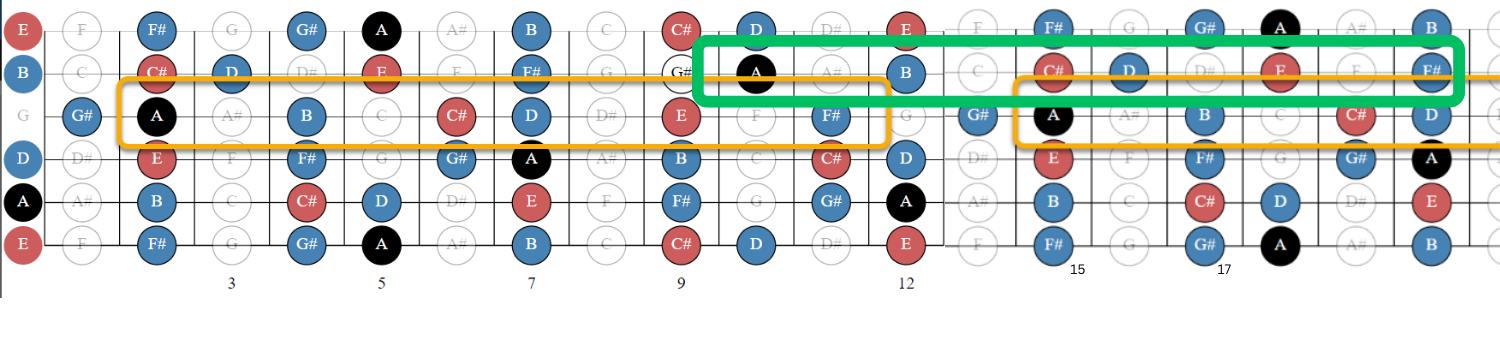

Here's the A-major scale; according to 'the method' here, it should then be possible to harvest almost any notes from this scale map to build-out harmonizations

Without a doubt, it's a lot of notes to digest, risking paralysis by analysis, so the notes are colored-in to indicate "priority", or natural tonal gravity, where a higher-priority means it suggests the underlying A-major chord more strongly

- Black/root tones

- Red/chord tones

- Blue/scale tones

- Transparent/chromatic tones

iv) How can the melody be harmonized?

This finally now sets the stage for assembling an arrangement, harmonizing the melody notes for Twinkle Twinkle, and experimentally figuring out what sounds decent and what may not sound as preferable. As a starting place, theoretically, the root-note should sound/accompany well with the melody; that's a high-probability place to start with this reharmonization. Also, if this root-note acts like an anchor, reminding the ear of the underlying root, it's suitable to play this as a low-pitched bass note.

Conveniently, there's that 5th-string open, which sounds-out an A-note without having to fret anything.

The sound that comes out is a consonant, unprovocative sound, where at least nothing clashes; and why would it? Given that the root is the most unclashing note one can play. Perhaps however it's desirable to tailor the now-bass-note, such that it marks the actual underlying chord progression. It's worth trying especially since the A-major, D-major, and E-major roots all happen to be available open-strings which don't need any fretting.

Part of the advantages of harmonizations is that it's in some ways easier to create intricate sounds without having to master difficult techniques such as alternate picking. Simply by hacking the underlying chords, which may even just be simple 3-note clusters, all of a sudden that's 3-notes to quickly play in a short amount of time. To press that advantage, at random perhaps it's worth trying to somehow include the 4th-string also.

In this imagined example, where one is just trying to spontaneously harmonize Twinkle Twinkle, it may be unknown which notes of the 4th-string to include. For that reason, it's always okay to treat this affair as alchemy and give each path a go. Here are 3 fretted-note possibilities for the 4th-string:

a) 4th-string: Option 1

b) 4th-string: Option 2

c) 4th-string: Option 3

Personally, the gentlest/warmest option feels like Option 1, so that'll be retained for the next build-outs that include the 2nd-string or 1st-string. And while this is now getting further into the melody's harmonizations, remember that these notes still derive fully from the A-major-scale; nothing more.

Scrolling back up to the A-major scale map, the 2nd-string open and the 1st-string open are also available notes within the scale; they'll be consonant too! These extra options create yet more potential iterations. Then, even by varying the timing of how the strings are plucked, yet more iterations can be created.

a) 2nd-string / broken

b) 1st-string / broken

c) 2nd-string / together

d) 1st-string / together

Hopefully, by now, the fog is clearing up a bit when it comes to these harmonizations. Granted, this way (among many) perhaps suits certain minds more than others, but it permits a logical approach for piecing together notes. Up until this point, that more-tailored bass-note approach was abandoned while the complexity of treble-side notes was explored, but that can be added back also.

To finish off this case #1 here's the tailored-bass, while still including some of the additions on the treble-side:

i) Tailored bass / 6ths

ii) Tailored bass / 5ths

Much like learning a board game by getting the 1st turn in, that's the 1st case in trying out this method of melody reharmonization! The next examples are really the exact same process, except posing scenarios where, when you randomly whistle a tune, grabbing the guitar, your starting melody note takes you to odd positions/strings of the instrument. Yet, no matter where the position is where you find yourself, it's always the same and just as methodical.

Case 2: Key of A / 2nd String

To prove the worth of this particular method, it should work for bizarre, uncomfortable positions on the guitar; in other words, even for unusual, seldom-played positions on the fretboard, it should still work, in doing its job for yielding fingerstyle arrangements -- otherwise it's not so much worth investigating. In that case, to hold it up to scrutiny, 2 uncomfortable positions will be experimented with here; the 2nd-string and the 5th-string, remaining in the key of A (for now).

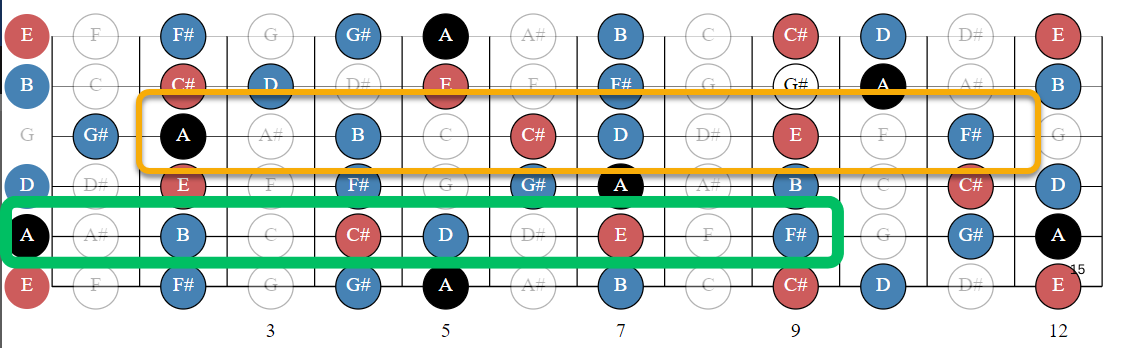

One advantage of playing horizontally (from low-to-high frets) instead of vertically (from low-to-high strings) is that the shapes are always the same. There's a scalability, where anything one learns horizontally can be played on any string of the guitar, or any stringed instrument for that matter.. violin, cello, upright bass, etc. To begin the process in this new position, at least, let the melody be the guide, and here it is circled in green on the 2nd-string. Notice how the shape is indistinguishable from where it was played on the 3rd-string; the fret spacing is the same.

With the key remaining in A, that means the same open strings are available; the open-A string, the high/low E-strings, and so on. What differs in this higher atmosphere are the available fretted-notes on neighboring strings. While the old-friends are far away, there are new-friends nearby, indicated by being colored-in. First off, it's worth getting re-oriented with the friendly open-string notes of the open-A and high-E strings.

Next, the 3rd string has many neighboring notes which can be played alongside the moving melody notes. While the differences in pitch make for an odd effect, the main point seems to still stand that the overall sound is still consonant; it still all works.

Finally, the bass-note can evolve from simply being a root-note drone to shifting with the assigned chord progression. Of course, this 'happens' to work here, since in the key of A, the I, IV, and V scale degrees are available as the open-A, open-D, and open-E strings; in other keys, this won't always be available so conveniently.

This method of reharmonization feels robust so far; it works in this bizarre case of playing Twinkle Twinkle fingerstyle with the melody on the B-string. But to keep testing its robustness, another crude test can be something equally as bizarre -- playing the melody on the bass A-string. Does the method still stand?

Case 3: Key of A / 5th String

Since the key is remains in A, again there's no need to: (i) determine the melody's root-note, (ii) underlying chord progression, and (iii) matching scales. Offering some ease, the alchemy step of (iv), piecing together a harmonization, is all that's needed to do!

Before anything, to get oriented, it's nice to see where the melody is now, to see what neighboring notes are available. On the 5th-string, the open-note is the root-note, A; from there, the melody of Twinkle Twinkle branches out.

Of course, the available notes on the open strings are unchanged, since the key remains in A. Beginning with some bass-notes grounding, the bottom-most E-string can be experimented with; after all, it's a red chord-tone according to the A-major scale diagram, so it should have some consonance.

For the sake of experimentation, one can even try using both E-strings; they're both usable per the A-major scale diagram. Plus, using that double-octave distance between the 2 E-strings, it's not often used as a focal point, so it can have a different type of sound.

Whether that type of sound is preferable is certainly subjective! However, for this 3rd case, this method of Twinkle Twinkle reharmonization seems to have stood up to the task! Thus far, it feels as though it's a robust way to navigate melody reharmonization in 'a few easy steps'. But what if the key of A is especially easy? What happens if different keys are chosen in different positions?

Case 4: Key of B / 3rd String

To ensure that nothing's 'gotten away with', it's good to carry-on with more odd examples, helping to ensure that this harmonization method should work in the future for other melodies which may require odd positions on the fretboard. In that spirit, and at random, here's a return to the melody on the 3rd-string, however the key will now be in B-major (not A-major)!

That tosses a wrench into the salad, refogging what was just clearing-up. However, when things get foggy, the old adage comes again to the rescue, "let the melody be the guide." Knowing that Twinkle Twinkle's melody starts with its 1st-note as the root-note, and given the 'project requirement' that the melody is played in the key of B off of the 3rd-string, one simply searches for the B-note on the 3rd-string. Once again also, the beautiful immutibility/scalability of playing horizontally across a single-string helps too; the range/shape of the circled melody notes is indistinguishable from the key of A.

What does however change are the neighboring friendly notes. No longer, for example, is the open-A note available; no longer do the open-E notes have the same tonal gravity (since they're now blue scale-tones instead of stronger red chord-tones). But by the same token, new friendly notes have appeared. Unsurprisingly, the open-B string is a very strong black root-note. That's perhaps a nice place to begin.

In the key of B, beyond the open-B string, there aren't as many friendly open-string notes, so, in the quest for adding more notes, it'll have to come from the bucket of fretted neighbor-notes. In that category, there's a lot to choose from; as an example, one can play 'trailing' notes on the high E-string; those notes that are within 1-fret of the fretted melody notes, playing those alongside the open-B string also.

Even for a fairly odd key for playing fingerstyle, the key of B, this harmonization method survived, yielding a result that sounds reasonable. To finally, drive the point home, how about playing in another less obvious, though slightly more commonplace key? In this case it shall be the key of F, but to make it more challenging, the constraint of no open-strings allowed will be added.

Case 5: Key of F / 1st String

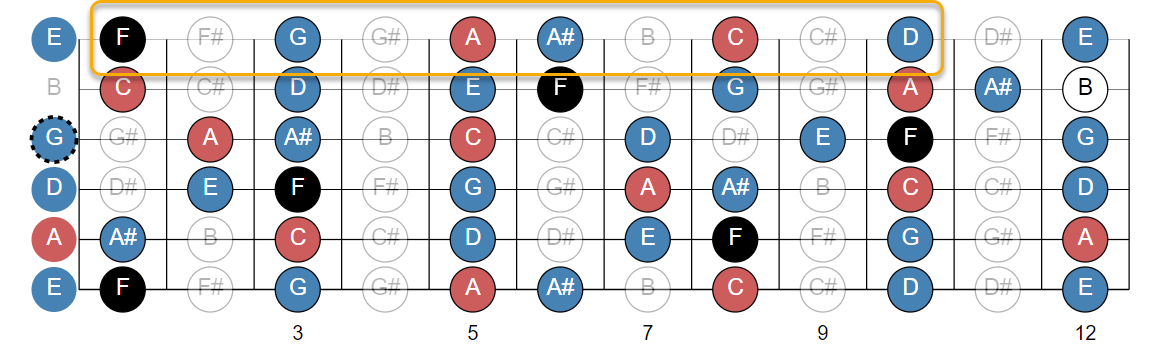

As a final 'litmus test', this will again scramble and refog the windows. When there's no visibility, what may the first step be? Relying upon the old wisdom, "let the melody be the guide." It's the key of F, with the melody on the 1st-string. Therefore, the first plan-of-action is outlining the melody notes.

Even though the melody is on a different string and in a different key, the range/shape of the melody (on a single-string) remains the same. Next, knowing that it's the key of F, the available F-major scale notes light-up a plethora of options for harmonization. First, it's worth beginning with the melody itself.

Recall that the challenge/constraint here is that no open-strings will be allowed. That doesn't really pose much limitations, because all the strings have available fretted-notes which can be trailed alongside the melody. As a perhaps mundane addition, what about adding in the octave on the 4th-string?

With both of those roots played simultaneously, there's not even enough room for it to sound "wrong"; however, the arrangement then needs some spice to add a bit of life to it. Helping to serve that purpose, here's the 3rd-string included, again with a trailing fretted-note to accompany the melody octaves.

While that's a simple way to satisfy the conditions, it does 'work'! Certainly, an unending amount of variations can be built off of this, finding alternative ways to tailor the notes to the underlying chords, reharmonizing the assigned chord progression itself, varying the picking patterns, and including or discluding other notes. Also, since this arrangement doesn't use open-strings it's 'movable', meaning one could shift the whole arrangement down a half-step, or up several frets, adding to the versatility.

Conclusion

The harmonization of melody notes opens a can of worms that goes as deep as the center of the earth. Adding an extra dimension from which ideas can be drawn, it can yield a cornucopia of possibilities, from creating a sense of 'simple complexity' for listeners, providing a basis for fingerstyle arrangements from nothing but a whistle of a melody, and the training to play a wide variety of repertoire.Specifically for the guitar, when it comes to fingerstyle playing, by following the approach of: (i) determining the root/tonic of a melody, (ii) identifying an underlying chord progression, (iii) scales which have consonant relationships to that chord progression... from there, the step (iv) can be taken of building harmonizations.. for any song, in any key, in any position. To make things easier, two tips include: (a) choosing where to play the melody at the outset, and (b) playing horizontally across a single-string.

PS: this isn't quite the first time Twinkle Twinkle has been used to explore the possibilities of reharmonization and arrangement. When a 25-year-old in 1781-1782, whose name was Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, felt like exploring this melody, the young man wrote down 12-variations that people still explore today.