How to read traditional music notation

Introduction

Much like calling people on the phone or reading books has withered with time, butted out by what's more convenient, such as sending texts or watching video clips, reading and writing music using standard notation has diminished with time also. Yet, much like how texting, while more convenient since it can be done in a loud auditorium, loses out in some aspects compared to calling people on the phone, just recording musical ideas with a voice recorder app or tablature losses out in some ways compared to writing ideas out in standard notation.

It's a mouthful to even get started with the advantages versus disadvantages of reading music via standard notation vs. tablature for the guitar. In many ways, the benefits of standard notation are not terribly obvious, making the discussion more difficult to convey; in fact, one often finds oneself in the strange position of aiming to convince others about the boons of standard notation. To lay things out more quickly (to get to how to actually do it sooner) these are some good reasons to revisit this older art.

- Standard notation is an abstracted symbolic representation of notes, so whether you have a saxophone in your hands or a guitar, if you understand how the physical instrument's notes map to the abstracted representation, you can play the same piece of music. On the other hand, tablature is a "lower-level", direct physical mapping of notes from the fretboard to the paper, so it's only readable specifically for the stringed instrument

- While the abstracted symbolic representation of standard notation makes for a higher barrier-of-entry, almost being a separate study in itself in parallel with learning the guitar, it actually depicts the rise-and-fall of pitches as well as visual representations of rhythms, allowing one to play pieces of music without having listened to the piece before. Whereas, with tablature, one has no indication of the rise-and-fall of pitches, since one has to read the tablature numbers and compute/calculate whether a number is higher/lower than another in order to anticipate the pitches. Also, it lacks an indication of rhythmic values, so there must always be an "a priori" audio reference of the musical piece in order to play it as intended

- While tablature allows for "repeated" pitches (such as the 0th-fret/high-E-string, 5th-fret/B-string, 9th-fret/G-string, etc), standard notation consolidates this into 1 location on the staff that represents this possible pitch. That means that when reading a piece in standard notation, one not only can visually "sight read" the piece, but one can also play the same piece in various positions on the fretboard, leading to more "freedom", while tablature locks one into a single-way of playing particular pitches, when in fact many alternative routes, which could be more efficient fingerings, may exist

Those are some of the core "pros" which standard notation has over tablature. Of course, tablature has its pros -- the clearest being that its "lower-level" representation of the guitar's fretted notes means that there's virtually no layer of abstraction posing any barrier-of-entry; it's wonderfully easy-to-use, which is likely why it's "won" the notation battle, much in the way that texting has "won" the communication battle against phone calls. But that's not to say that texting is better in every way than phoning people. In the same vein, standard notation, like phoning people instead of texting, carries many other boons such as opening the door to playing music of other genres (classical, flamenco, etc), and even unexpected benefits such as fretboard memorization. While some may find this dubious, and that's okay, much like knowing the name of someone helps you remember them, knowing the abstracted "note names" for each fret helps one surprisingly remember all the frets on the fretboard also. It's quite a commonplace goal for people to memorize the entire fretboard, freely playing from any position, gliding up-and-down the neck with little inhibitions; it's strange to realize that actually knowing the note-names is a key way to accomplish this, instead of memorizing laborious systems and grid patterns.

It's probably unnecessary to really delve into that "debate" between standard notation vs. guitar tablature; those interested in learning standard notation have their reasons, and those uninterested in it have their reasons also.. adding more to the discussion, it's likely to do nothing more than encourage those on each side to dig their heels in even more. Moving onwards, for those interested in gaining some awareness of standard notation, what's a workable regime to crash-course one's way through the basics? A single "best" way is unknown, at least to this author, but answering the question of what's the "worst" way, then avoiding that 'worst way', is far easier, and at least offers some to-do-nots.. the worst way to learn the basics of standard notation is perhaps to actively ignore any mention of it. Therefore, the goal of this guide will be to at least mention some aspects of standard notation, the aspects most apparent to really use it, which should at least be better than the most anti-optimal path forward.

The contents of this guide

- Time signature

- Bars

- Music staff

- Clefs

- Note values/rhythms

The aims of this guide will be to convey the important things to at least bridge the main gaps between this "abstracted representation" of notes from the standard notation staff to the guitar's fretboard. With that foundation, at least one ought to be able to fight-through a piece of standard notation, without being left simply not knowing what certain symbols mean.

Time signature

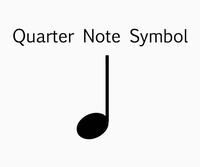

It's rather arbitrary, deciding where to start when introducing standard notation, but given that rhythm & feel is such a vital aspect to music, beginning with what's dubbed the "time signature" seems like not the worst place to begin. In essence, one can translate the term "time signature" into: (i) how the beats are grouped together and "felt".. such as in a 2/4 polka, versus a 3/4 waltz; and (ii) the assigned time-value of a quarter-note.. (which are always the black, colored-in notes with straight-lined-stems coming off of them.)

Pretending that this is all being learned from scratch, the diagram of notes below this paragraph "should" be incomprehensible. Except, the numbers "4/4"; this is the time signature. It comprises of: (i) an upper number and (ii) a lower number. In the case shown by the diagram below, the upper and lower numbers are "4". However, each number represents unrelated things. What might those 'things' be? Exactly what was mentioned before; the upper-number describes how to "feel" the music, in groups of 2, 3, 4, 5, etc beats; the lower-number is more to-do with literal notation -- the value of what's called the "quarter-note", which then implies the time value of value of "whole notes", "half notes", "eighth notes", etc.

i) What's the top number

The top-number indicates how to "feel" the music, or perhaps better said -- how to "count" the music. For example, one can listen to Bill Evans' Waltz for Debby which can be "counted" in groups of 3-beats. Then, there's Dave Brubeck's Take Five, which can be "counted" in groups of 5-beats. Then there's All Blues by Miles Davis which can be "counted" in groups of 6-beats. They're known to be in the time signatures of 3/4, 5/4, and 6/8 respectively... ignoring the lower numbers for now, the upper-numbers clearly denote that grouping which one can sense.

ii) What's the bottom number

The bottom-number tells you the time-value of a single-quarter note when it's written down. For example, any piece of music with a lower-number of "4", such as "2/4", "3/4", "4/4", "5/4", "6/4", etc.. means that a single-quarter note accounts for 1-beat or 1-count. From there, one can reason that: (i) a whole-note accounts for 4-beats, 4-counts; (ii) a half-note accounts for 2-beats or 2-counts; (iii) the quarter-note again accounts for 1-beat or 1-count; (iv) an eighth-note accounts for a 1/2-beat; (v) a sixteenth-note accounts for a 1/4-beat... and so on. It somehow all works out in powers-of-2.

However, what if the song is written in the time signatures of "2/8", "3/8", "4/8", "5/8", "6/8"? That cuts the value of the quarter-note in half. Therefore, a single-quarter note is instead valued at half-a-beat, which then implies recalculated values for whole notes, half notes, eighth notes, and so on. Fortunately, most written music one encounters either has lower-numbers in the time signature of either "4" or "8", so this normally isn't a huge mental obstacle to digest. Instead, it's enough to mainly know that the bottom-number is, in other words, like a variable which alters the time-value resolution of the quarter-note, and therefore the other types of notes.

Bars

Given that the top-number of a time signature tells the reader how to "feel" or "group" the beats of music, the bars/barlines visually encapsulate those groupings. In a technical sense, they're not actually needed; one could play a piece without barlines, since the rhythmic/time-values are given in the symbols of the notes & rests, but similar to separating 4,000 words into paragraphs, rather than a giant wall of text, barlines assist with legibility/readability.

As an extra tidbit about bars, usually it's a nice favor when transcribers/notaters of sheet music consistently follow a regime of, say, 4 bars per-line; it's like an extra umph of legibility, though this isn't always the case and that's fine too.

Music staff

To be honest, it may have been best to actually start by talking about the music staff; if one tried to be poetic, the music staff might be described as the, "blank canvas upon which one can transcribe one's musical thoughts." As far back as the days of Ancient Greeks, people have tried to transcribe musical pitches on paper; yet, this settled upon style of the music staff came about during Medieval times, allowing for a visual representation of the rise-and-fall of pitches; if notes are higher-up on the staff, they're higher-up in pitch; if notes are lower-down on the staff they're lower-down in pitch.

Of course, while this is meant to be a guide for guitarists, recall that these lines do not correspond to the physical strings of the guitar, which would be a "tablature staff".. for starters, it only has 5-lines, whereas tablature has 6-lines. This traditional staff doesn't physically map to any particular instrument; instead, a different way to think about it is that the music staff maps to 'pitch' itself, so anything that creates sounds can abstractly relate to it, whether it's a guitar, harmonica, or blue whale.

Although, some caveats ought to be mentioned before generalizing the music staff to being able to map any pitch.. it's limited to the western-music-culture of dividing pitch into 1/2-steps, also called 'semi-tones'.. this equates to 1-fret on the guitar, or an adjacent black or white key on the piano. However, theoretically one could redefine custom music staffs which account for the "micro-tones" in between 1/2-steps if it was really desired.

Clefs

In the western-music-style which has developed since Medieval-times, the distilled notes are just 7 in-number, and for easier recollection, they're alphabetical; A, B, C, D, E, F, G.. then it repeats. Remember that the staff lines maps to pitch.. the next question is then: what note-letter does each line correspond to?

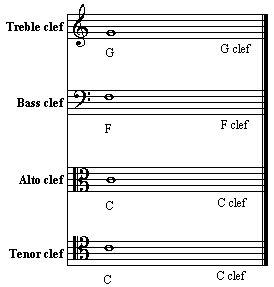

To answer that question, it depends on what's called the "clef"; there are 4 clefs which exist, and each clef assigns different letters for each of the music staff's lines/spaces. Once one knows the note-letter of a given line or space of the music staff, one can work out the note-letters of the rest of the music staff, since each line or space increments or decrements by 1 of the 7 alphabetical letters.

For example, the diagram below shows the treble clef. As its name suggests, it's often-used for treble-instruments, such as the guitar. As a nice visual reference, one can see that the second-staff-line from the bottom is encircled by the treble clef's circular swirl; that's an oft-used reference line for the G-note. From there, the lines and spaces increment/decrement by 1 note-letter. The space adjacent & above the G-note line is the A-note; the space adjacent & below the G-note line is an F-note. Then, the line adjacent & above the A-note space is a B-note; the line adjacent & below the F-note space is an E-note.. etc.

Mainly, it's enough to digest that each clef designates: which note-letter (meaning 'which pitch') maps to which staff-line, where the note-letters symbolize pitches. (It's easier to call a certain pitch "F" instead of 2959.96 Hz.)

Note values

It's one of the great, unmatched boons of standard notation that one can visualize, even look ahead, and anticipate the time values of notes (and rests). The standardized time-values of notes happens to traditionally be written in "powers of 2", for example 1/32 notes (thirty-second notes), 1/16 notes (sixteenth notes), 1/8 notes (eighth notes), 1/4 notes (quarter notes), 1/2 notes (half notes), and 1/1 notes (whole notes). This range of time-value options seems to satisfy the needs for most musical ideas. Each "power of 2" note-value has a unique visual "look", which are shown below:

i) Whole notes

ii) Half notes

iii) Quarter notes

iv) Eighth notes

v) Sixteenth notes

vi) Thirty-second notes

Note value modifiers: dots & ties

Adding more options to the notation palette, there are 2 extra ways to convey a note's time-value -- through dots & ties.

i) Dots

By placing a dot to the right of a note symbol, it's instead valued at 150% of its original time value.

ii) Ties

By tying notes together with an arch-type of connector-line, the note values add-together and merge as a single-note.

Multiple notes can be tied together, but they have to be the same pitch.

Rests

The saxophonist Jimmy Heath opined that music is nothing but, "lines and spaces"; similarly, Miles Davis sometimes suggested that his bandmates play, 50% of the notes they usually play. In other words, blank/negative space ironically seems to get more 'in focus' as one progresses on an instrument. In the syntax of traditional music notation, this is illustrated with 'rest' symbols. Similar to note-value symbols, rest symbols imply their time-value also.

And that's the final "note" for this guide when it comes to acquainting oneself with traditional musical notation. It's itself likely leaving many blank/negative spaces that no doubt need back-filling, but at the very least hopefully it thins the fog somewhat when it comes to this aged language.

Conclusion

Going through the boons of standard/traditional notation, it becomes clearer how this old-fashioned style of notation has features which its younger offspring, guitar tablature, isn't quite able to convey, whether it's the visual representation of pitch, the time-value of notes, or the presence and time-value of rests. Not only that, but traditional notation unshackles stringed-instrument players from having to play particular pitches at exact points on the fingerboard/fretboard, permitting freedom-of-choice on top of the facility to "sight-read". Of course, one may wonder: "if this notation brings such benefits, why has guitar tablature ousted it from its place?"

Most likely, it's because traditional notation is a symbolic, higher-level abstraction, mapping sounds to a visual representation of "pitch"... whereas tablature is a raw, lower-level non-abstraction, mapping sounds directly to the physical fretboard... the barrier of entry of traditional music notation is therefore higher, practically a separate study in itself, parallel to the study of the instrument. Favoring convenience, traditional music notation is often discarded or overlooked, yet much like how phone calls are overlooked in favor of texting, it doesn't mean that phone calls are worse in every way than texts.. in fact, in many ways phone calls are far superior, and the same goes for traditional music notation.

From here, now knowing a bit more about traditional music notation, most of this information will likely wash away if not applied soon. Some paths forward could include: (i) notating a musical idea with tradtional notation, or (ii) learning a piece of music through traditional notation. With experience, one can better realize if traditional notation can bring benefits worth exploring further.